When you have queers simultaneously fighting against a war and for the right to fight in it, the end of the world seems nigh.

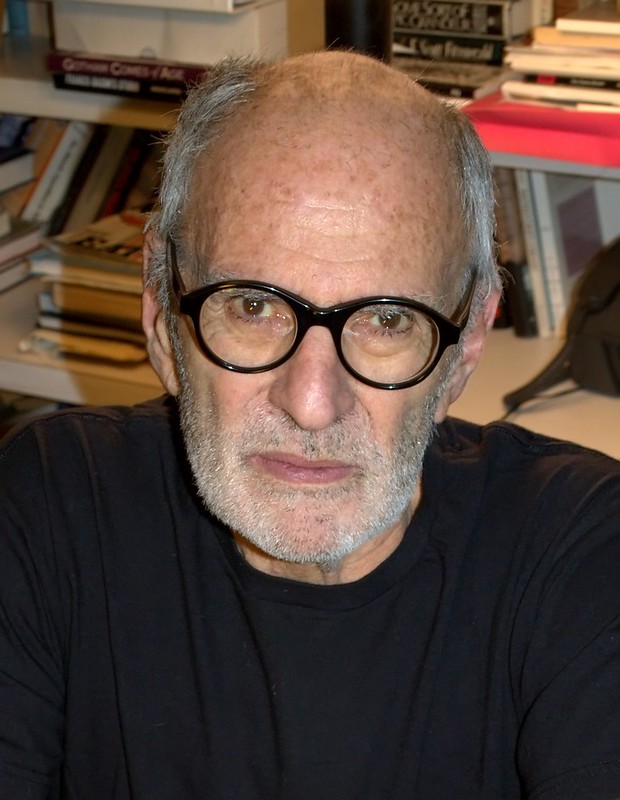

By the time you read this, a vastly over-inflated moment of queer hype will have sputtered and gasped to its inevitable end. The events following Larry Kramer’s March speech now constitute a tempest in a teacup. But they did draw out some strong emotions, not all of them articulated in the kind of grandstanding we witnessed in the photographs of self-proclaimed AIDS activists in ACT UP t-shirts.

On March 13, 2007, the 20th anniversary of ACT UP, Larry Kramer stood up at the LGBT Center in New York and delivered a speech. As is his wont, Kramer launched a number of screeds at various targets, resulting in a jumbled mess of contradictions that gave birth to equally contradictory bits of “street activism” in the following weeks. Among his points: a denunciation of the Pentagon’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, a call for hate-crimes legislation, and a plea that US same-sexers be allowed to sponsor their non-citizen partners for citizenship.

Two days later, a reported 250 people, including Kramer, marched on the Manhattan Armed Forces Recruiting Station, protesting the remarks of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Pace, who had declared that homosexual acts were immoral. Protesters carried posters announcing themselves as “fabulous,” along with flags denouncing DADT. Matt Foreman, executive director of NGLTF, was arrested for obstructing traffic.

On March 29, 500 people marched in Times Square as part of a supposedly rejuvenated ACT UP Army/Queer Justice League (at the time of this writing, the name is still disputed), calling for a single-payer health care system and drug price controls; 27 people were arrested.

Power to the (Tupperware) Party

Larry Kramer stands at the center of all this brouhaha, feted as the spark that re-ignited queer street activism. In an interview with Rex Wockner, he deplored the moribund (to him) state of gay activism, “Please don’t wait for others to do anything! There once were ACT UP chapters in dozens of American cities. People just got together and did stuff. All across America. Do it again, for all our sakes! Just call a Tupperware party and say to your friends, ‘OK, what can we do this week?’”

I’m sympathetic to Kramer’s frustration at the paucity of street activism. Americans today occupy a political landscape dominated by the virtual mobilization of groups like MoveOn.org and online petitions have taken the place of street pro-tests. Some of this is powerfully conducive to mobilizing dissent quickly and effectively. But in terms of actively resisting state power and intervention– whether in matters of war or the defunding of public schools– nothing quite matches the heady and potent symbolism of an angry and strident street protest.

It’s worth remembering that Kramer’s anger helped mobilize ACT UP to disseminate a wider social critique of the rapacity of Big Pharma, its opaque system of drug trials, and the lack of access to new treatments. ACT UP, more than any other organization, radically transformed the way people related to their doctors, when the medical establishment either refused to treat AIDS patients or denied their right to know about, among other things, the effects of medications and treatments. The group created an unprecedented political cadre of patients and supporters who made governments far more accountable to sick people.

But what do Kramer and his ACT UP Army/Queer Justice League call for, exactly? Let’s consider the fact that the Kramer-led band was fighting for an end to DADT and against a war that it fervently describes as “immoral.” When you have queers simultaneously fighting against a war and for the right to fight in it, the end of the world seems nigh.

Next is the call for the expansion to federal hate-crimes legislation to include sexual orientation and gender identity. To use Kramer’s own words out of context: this is progress?

Hate-crimes legislation only perpetuates the idea that justice should be determined by the identity of both victim and aggressor. These laws also punish thought and belief, in ways that should frighten queers in particular. They increase the scope and brutality of the prison-industrial complex to include those whose sentences are lengthened because their crimes are deemed worse if they can be proven to have thought or believed badly of their victims. In specific cases, as in the 2004 Ohio murder of Daniel Fetty, the ideology of “hate crimes” can allow prosecutors to ask for longer sentences or the death penalty, even where no specific hate-crime law exists.

And then there’s immigration. Kramer’s concern here has to do with what groups like Immigration Equality (IE) and Out 4 Immigration (O4I) refer to as “bi-national” couples– people apparently tragically torn apart because one partner is not a citizen and cannot be sponsored by the other for immigration benefits, as straight married couples can. As Kramer puts it, “Do you have friends in love with partners forbidden from entering America? To be separated by force from the one you love is one of the saddest things I can think of.”

Actually, I can think of much sadder things– like uncoupled immigrants being forced to return to the alien landscapes of countries they left long ago, wrenched from the kinship networks they have formed in the US. Or being forced to go underground because they’d rather do that than run the risk of entering into any relationship. I could go on, but even such counterpoints wouldn’t get at the heart of the immigration issue: neoliberalism’s naked need for (and constant exploitation of) cheap, readily available labor.

Both IE and O4I support UAFA, the Uniting American Families Act, which purports to “fulfill the promise of family unification in the US.” But as those working on immigration know too well, the biggest impediment to progressive reform is the fact that so much of immigration law is family-based. The focus on family blinds us to the realities of the massive global exploitation of labor and the severe economic disparities created by the US which cause millions of undocumented laborers to enter the borders in the first place. The rest, embodied in narratives about love torn asunder, is mere affect.

I understand this hunger for street activism, and I give credit to ACT UP NY for raising the issue of health care. I want more public anger against injustice, and I would like to demolish systemic privilege and economic inequality. But none of that is challenged by the recent fracas and calls for action issued by Kramer and his ilk. Ironically, they call for exactly the kind of institutions (marriage/coupledom, hate-crimes legislation, DADT) that keep privileges in place, wrapped in the insurgency of a rainbow flag marched across Times Square.

All of which only proves a sad fact about queer organizing today: queers are only moved to act up in public to prevent their divestment from economic privilege. Meanwhile, the economic inequality that is at the root of the tremendous injustices of a broken health care system, a flourishing prison-industrial complex, and the brutality of a US-led series of wars for oil is left unchecked.

Do queers today have an expansive notion of social justice, outside of the merely “fabulous” and strident drama that rings so hollow today? What kind of social justice movement, as opposed to a queer justice movement, can come out of this? Is a militant set of actions necessarily a radical one?

Originally published in The Guide, June 2007

See also my “Larry Kramer, The Imitation Game, and the Problem with Gay Exceptionalism.”