Excerpt: Punk’s political power once lay, at least in part, in its refusal to live by categorizations, and its defiance of the imperative to grow up, settle down and pretend that there is nothing new to learn or live for after a point.

Gorsky Press; 188 pages.

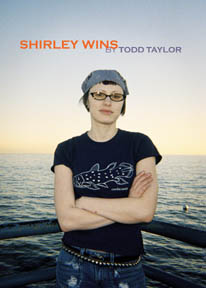

Shirley, the eponymous heroine of Todd Taylor’s new novel, wants to throw a pumpkin—really, really far; she wants to win the Second Annual Pumpkin Chuck. Prize money and fame aren’t the motivating factors. What Shirley wants to do is create a “weapon of mathematics,” a demon of pure physics mastered and materialized by her own hands to throw a pumpkin far enough to win the competition.

Shirley lives with her granddaughter, Rachel. She works in an office where she isn’t just “used to being considered average … she [counts] on it.” All that her co-workers know about her, because of her annual Christmas gifts to them, is that she loves to knit. Shirley and Rachel live quietly together, and the latter is consumed by her love of punk and bio-genetics (the kind practiced by Gregor Mendel, not the corporation GM).

Shirley’s passion is physics, one that she had to submerge 45 years ago because, as Taylor puts it un-tragically, “Life has a way of folding up what you really like, putting it in a garbage sack, hauling it to the local dump, and handing you a job in its place.” Her long-buried interest comes to life one day when she finds an abandoned physics textbook. She takes it home to devour its pages and those of more books borrowed from the library. Fate intervenes a few days later, with an article about the pumpkin chuck printed on the other side of a full-page coupon for lasagna.

From there on, Shirley Wins is an account of months of hard work and countless experiments, mostly carried out in secret. The task ahead of Shirley is, on the face of it, relatively simple: To throw a mid-sized circular object through the air. But this requires an exact understanding of basic and complex matters of physics—the exact curve of the spiral of air around the pumpkin to maximize velocity; the width and depth of the pipe that hurls it; and so on.

Shirley Wins celebrates the expertise accumulated by people as they go about their daily lives and jobs. Stoobs, the man who helps Shirley make a critical part of the machine, mulls over the history of the combustion engine as he drills and shaves metal. She enlists Rachel’s help and the young woman goes about engineering pumpkins with a sufficiently hard shell and the exact required size. Shirley can make connections between knitting, at which she is an expert, and welding, which she must teach herself. The novel is as much a meditation on the nature and rhythms of work and the patterns through which we get projects done as it is about Shirley’s path to the pumpkin chuck.

On the way, Shirley gets connected to her body in unexpected ways. She’s now vulnerable to sharp steel and pipes that blow up in her face. At one point, a test catapult pulls up suddenly—leaving a long, straight and bloody line all the way down her face and body. It also leaves Shirley momentarily dissociated: “She felt like she was subconsciously measuring herself for a highly calculated slaughter, like old recipe books that explained where to cut for each piece of meat available from a cow.”

The book is filled with such sharp but unobtrusive details. It’s an account of the unconventional, intimate and sometimes fleeting relationships between people who unite for a common cause. None of this is maudlin—Rachel and Shirley love each other deeply, with no heed to the years between them, and without sentimentality. When this book came by my desk, it was described as a novel by a punk-rock author and I wasn’t sure, at first, what that meant. Punk’s political power once lay, at least in part, in its refusal to live by categorizations, and its defiance of the imperative to grow up, settle down and pretend that there is nothing new to learn or live for after a point—in which case, this small jewel of a novel is as punk as it gets.

Originally published in Windy City Times, 9 May, 2007

Don’t plagiarise any of this, in any way. Read and memorise “On Plagiarism.” There’s more forthcoming, as I point out in “The Plagiarism Papers.” I have used legal resources to punish and prevent plagiarism, and I am ruthless and persistent. If you’d like to support me, please donate and/or subscribe, or get me something from my wish list. Thank you.