“I’d been upstaged, demoted from protagonist in my own drama to comic relief in my parents’ tragedy.”

Houghton Mifflin; 240 pages

On July 2, 1980, when she was 20, Alison Bechdel’s father, Bruce, was killed by a truck as he crossed a road. One version of the story is that he committed suicide by deliberately putting himself in front of the vehicle. Another is that he saw something that startled him at the side of the road and jumped backwards, only to be hit. If that were true, Bechdel writes, perhaps he recoiled from the sight of a snake—perhaps a snake like the one she had once seen in the woods, a six-foot-long reptile sipping from a spring.

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is a dense and recursive memoir about Bechdel’s relationship with her father. Events are relayed with multiple possibilities of what could have been. It’s also a “graphic novel,” a term that doesn’t convey the depth and artistry of this lovely and incisive book.

Alison Bechdel is long familiar to Windy City Times readers as the creator of the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, which is about a motley crew of lesbians in various entangled relationships. Fun Home is nothing like Dykes, which is mostly a good thing. In the last few years, Dykes has become overly didactic and tries too hard to convince us that lesbians are still ironic and willfully postmodern.

With Fun Home, Bechdel creates a text without artifice or needless commentary. Characters are generally uncommunicative with each other but their rich interior lives form the bedrock of the narrative. Panels convey silence and space with concise drawings; text is positioned above or on the sides as people walk with their secrets.

The secret at the heart of this story is, like every good family secret, really no secret at all. It’s a long-suspected truth that simmered under the surface of Bechdel’s childhood in Beech Creek, Pennsylvania. Bruce Bechdel had numerous affairs with local teenage boys and men he met on his excursions out of town. When Alison Bechdel came out to her parents in a letter, her disclosure prompted her mother to respond, “I have had to deal with this problem in another form that almost resulted in catastrophe. Do you know what I am talking about?” Alison writes back, “What catastrophe?” It’s significant that her response is not to ask what the “problem” had been but to ask about the end result, the “catastrophe.” As if to say, “I know what the “problem” was, but when did it really become something we couldn’t ignore?”

In the hands of a lesser writer and artist, this might have been a narrative about betrayal, anger and barely-contained homophobia. In Bechdel’s acutely-rendered panels, such moments are simultaneously hilarious and solemn. Key events, in this case a disclosure met with another, appear more than once. Each time, they are rendered even more complex and coupled with Bechdel’s dry wit: “I’d been upstaged, demoted from protagonist in my own drama to comic relief in my parents’ tragedy.”

Fun Home is about living with the truth in plain view and learning to work around it. The Bechdels were not conventionally close, but were nevertheless exceptionally communicative; their many letters were carefully-crafted commentaries on the world and repositories of the emotions they would not display otherwise. They are drawn with their eyes warily half-closed, slightly hunched over in carefully-composed attitudes of detachment. Their guardedness had its advantages; it meant they could dig into their creativity without feeling the need to answer to the world.

Bechdel grew up with a father who was simultaneously gifted, kind, aloof and cruel—a man who spent years restoring their crumbling Victorian mansion into a perfect setting for an idealized version of a family.  His physical presence did nothing to reassure her of his proximity to her. Or, as she writes in a panel where her child-self cuts the grass on their meticulously tended lawn, “I ached as if he were already gone.” That writerly ability to understand untold and hidden stories and to fictionalize experience may well be her father’s greatest gift to her.

His physical presence did nothing to reassure her of his proximity to her. Or, as she writes in a panel where her child-self cuts the grass on their meticulously tended lawn, “I ached as if he were already gone.” That writerly ability to understand untold and hidden stories and to fictionalize experience may well be her father’s greatest gift to her.

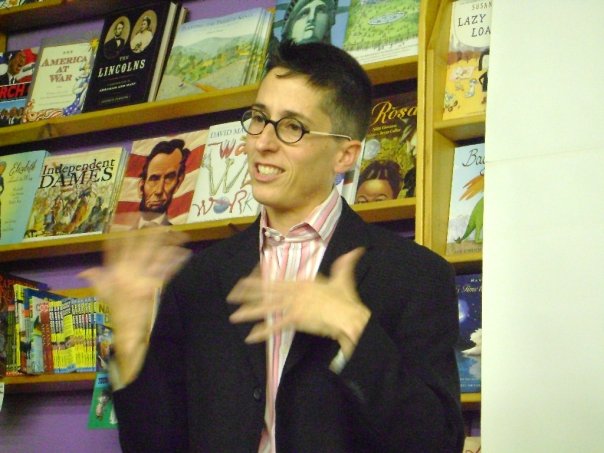

Photo of Alison Bechdel by Yasmin Nair

Photo of Alison Bechdel by Yasmin Nair